Interview: Lorenzo Redaelli, Creator of Mediterranea Inferno

Where we talk (among other things) about bank advice, creativity, infernal pop, and young artists just keeping their heads above water.

Welcome back to Artcade, the mic for interviews you weren’t expecting. Sure, in the last episode, I hinted at a surprise, but I doubt anyone expected to encounter Artcade’s very first interview. The first one! Which suggests there will be more. Isn’t that exciting? No? Probably because you haven’t read it yet. We’ll talk again at the end. In the meantime, if you haven’t already, check out last week’s episode on Mediterranea Inferno, the game created by Lorenzo Redaelli, whom we’re about to chat with. Enjoy the read!

Hi, Lorenzo. Thanks for accepting Artcade’s invitation.

It’s my pleasure!

First off, congratulations—you won Best Italian Game at the Italian Video Game Awards, and just a few months earlier, you received the Excellence in Narrative award at the Independent Games Festival in San Francisco.

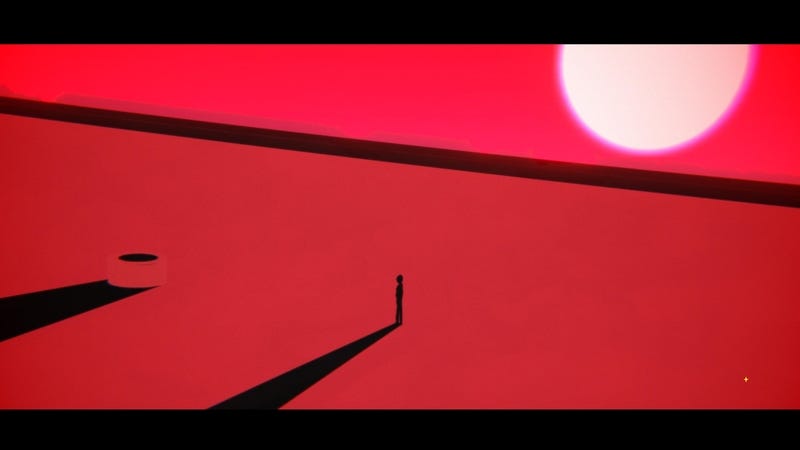

Let’s start with that. Mediterranea Inferno is about three young men who get back together—or at least try to—after the emptiness left by the pandemic. Your first game, Milky Way Prince - The Vampire Star, was a visual novel. Given the importance you place on narrative, let me ask: why is Mediterranea Inferno not a novel?

I’d say that for the kind of stories I wanted to tell, I needed a “brain” capable of managing multiple situations. In both games—although for slightly different reasons—I needed many sides of the same coin, many different, parallel realities that coexist to form a complete narrative. I wasn’t interested in presenting my direct perspective; rather, I wanted to create a system in which the characters could explore one of my hypotheses. My perspective mostly emerges in the constraints I put on this system.

Meaning in what the player leaves behind, in what they choose not to see.

Exactly. So really, for these kinds of stories, the difference between a novel and my work is that I needed multiple visions, multiple points of view. My first game, in my opinion, should be played only once—it’s like those quizzes in teenage magazines: you finish it and get what you deserve. Mediterranea Inferno, on the other hand, is a game that should be fully explored because the most interesting aspect is seeing the differences in the characters’ psychologies. More than the story, it’s about observing how certain psychologies adapt to specific situations.

Where do you start when creating a game?

I definitely have a general outline in mind, although I don’t like starting from a set story because I get bored quite easily, and these are very long projects—it took two and a half years to make Mediterranea Inferno. I need to entertain myself too, so I don’t lose interest in the project. So I had certain guidelines, visions of how the endings might be, but the protagonists’ journey was also a journey for me.

Does composing the game’s music help inspire you?

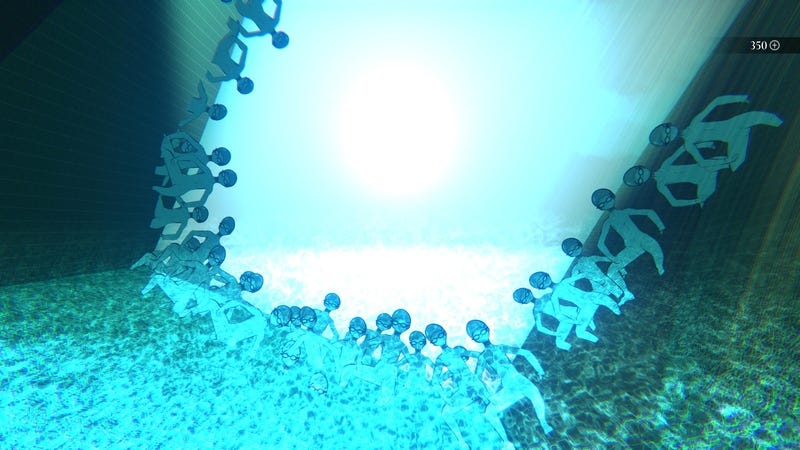

Yes, music helps me a lot. Whether it’s someone else’s music or mine, it gives me an initial kind of imprint—the atmosphere, a feeling I want to pass on to the player. Before certain chapters, I wrote the music first to set the right tone. Unlike a book, where you only have text, a game has lots of multimedia elements, and depending on the moment, you can focus on whichever aspect you want. Sometimes I felt that the writing needed to be more fleshed out, so I wrote a lot. Other times, I focused on the visual side. Some parts of the game needed a more immersive, almost sensory approach.

During the mirages, for example, you switch to a more intimate register. Essentially, you use different tools to achieve the result you want. With a novel, you’d be limited to written words—and from what you’re saying, you’d likely get bored. It’s also a way to vary your work and the artistic form you’re exploring.

Absolutely. I think if I didn’t do that, I’d bore the player too. That’s why my resolution for my next game is to ensure it’s still narrative overall, but without using text.

All right, so tell me more about your next project. Do you already have some ideas? Are you still experimenting?

It might never become my next game, but the one I’m working on now is in 3D, and that’s already quite new for me. I’m mostly in a technical phase, figuring out whether the idea I have can hold up—whether it works.

A 3D narrative experience, then? Something like Firewatch?

Not exactly… it’ll be a surprise.

You’re right—I was trying to get a scoop.

No, no, it’s just that I don’t even know if what I’m picturing is feasible, so I don’t want to get ahead of myself [laughs]. Let’s just say Mediterranea Inferno brought to light all the problems I noticed without proposing any solutions. With my upcoming projects, I want to try to offer solutions or at least alternatives.

Mediterranea Inferno is also quite brutal. If you don’t favor certain characters—if you don’t let them eat the fruit to experience the mirage—you’re basically condemning them.

That was the mindset I had at the time; it would have felt disingenuous, after all that happens, to present a positive outcome. Even though it’s a very universal game, Mediterranea Inferno focuses on a very specific social bubble.

I think that’s part of its originality: you portray a homosexual, queer world, but typically when a story features that element so prominently, you’d expect it to become the central theme. Instead, you depict it vividly, realistically, very sincerely—yet it’s more like part of the setting. The core theme remains: three guys trying to pick up their lives after the pandemic’s void.

Exactly. That’s because most mainstream queer output is designed for a straight audience. Usually, it’s a way to push acceptance or normalization, whereas I simply described a reality that surrounded me, especially at that time. Plus, I knew I’d be speaking to an international audience, since the video game market is international. I could have gone the Guadagnino route, or done what the Japanese do—just lay out their worldview and let you deal with it—and that’s the method I chose.

The game is crammed with references.

Yeah, a ton of them. That’s because I had to measure myself against—or rework—an entire cultural collective imagination. I intentionally added many references because I wanted to see what was still relevant and what had aged poorly or even turned toxic. There’s a heavy dose of deconstruction around what it means to be Italian, too.

You mentioned multiple projects. Besides prototypes for future games, are you working on anything else? Given the scope of Mediterranea Inferno, I could picture you creating a graphic novel or a music album—anything seems possible.

I’m making music at the moment. I think my new album will be out in three or four months. It’s completely guerrilla-style, self-produced, with friends who helped me polish it because I’m a bit of a mess.

Genre?

I’d call it deconstructed pop, since it takes elements of mainstream genres, picks them apart, and then, if something works, I toss it into a more unsettling context, creating an almost… infernal soundscape. But at the same time, it’s pop.

“Infernal pop”? I’ve never heard that term and I already know I’m going to listen to it.

For me, making music is like therapy. It helps me relax—every time something happens, I write a song. Releasing it much faster than a video game also lets me process personal issues more quickly.

Speaking of Mediterranea Inferno’s release—I’m not sure if you can answer this, but it’s had critical success and garnered plenty of media attention. Is it also paying off in terms of sales? Are you managing to live off your art?

Well… so-so. I’m floating by on artistic work. My friends who are my age (and who are also my favorite artists) produce work I identify with; they’re unbelievably talented… and I’m the richest among them, which says a lot! We’re all barely staying afloat. Italy it’s not the kind of country where you can survive by making art, especially if you’re young. It’s really tough. There should be a way to be supported and recognized, regardless of sales. The government should find a way to protect artistic endeavors. It would probably increase sales, too, which would benefit the state in the long run. We need a system where an artist feels secure and knows they can take risks. Because in Italy, pursuing art has basically become Russian roulette.

I was just reading how Ireland’s government supported the growth of its literary scene, leading to internationally acclaimed writers like Sally Rooney, Paul Lynch, Anne Enright, and many others. They didn’t do anything wild—cut some taxes, provided funding so they could pay their bills. When you’re young, you might have dreams of getting rich, but for an artist, it’s often enough just to make a living creating art.

That’s me to a T. Everything I earn goes right back into making music and advancing my projects. And besides living, I’d also like to maintain my dignity through art. When I went to the bank and told them I was an “artist,” they said, “We’ll put down ‘student.’” Tells you everything you need to know.

Amazing. Okay, let’s end on a lighter note—what are you playing these days?

I have to confess I’m not a hardcore gamer. As we said, I’m hyperactive, so if I spend too much time reading or playing a game, I feel guilty—like there’s this Catholic notion of “if I’m not producing, I’m worthless.” Still, I do play to switch off, especially in summer. I recently picked Red Dead Redemption 2 back up—I already played it last year. Plus, every time I go through a breakup, I dive into a big, never-ending game to get over it… so there’s one every summer [laughs].

Let’s hope the next giant game you play is Red Dead Redemption 3, which will take ages to come out. From what you’re saying, gaming helps you breathe.

Right. My gaming choices are sort of random. But you know what I play a ton of? Planet Coaster, a roller-coaster management sim. I get lost in it for, like, 300 hours a week. But that’s not even a game—it’s software, it’s a job!

Lorenzo, we can’t wait to listen to your new album and play your next game as soon as possible. Thanks for chatting—it’s been really interesting.

Thanks to you and Artcade’s readers—ciao!

My last two coins

Thank you for joining me for Artcade's first interview! If you enjoyed it, don’t forget that you can share it using the button below. Until the next episode, ciao!